When shall innovation come? A rejoinder to Jacobin’s Red Innovation issue

This month’s Jacobin Magazine tackles the subject of technology, and in it, one article titled “Red Innovation” was an interesting read, but it displays the countless pitfalls of thinkers who are not trained in economics but proffer on capitalism. Here is one section:

It’s no surprise that Apple’s tremendously successful line of products — iPads, iPhones, and iPods — incorporate twelve key innovations. All twelve (central processing units, dynamic random-access memory, hard-drive disks, liquid-crystal displays, batteries, digital single processing, the Internet, the HTTP and HTML languages, cellular networks, GPS system, and voice-user AI programs) were developed by publicly funded research and development projects.

It hasn’t been the dynamics of the market so much as active state intervention that has fueled technological change.

And yet, if Apple had not developed those products for the masses then they would simply be nice ideas in the pages of some fraying journal. Production is one side of the market of which research is a part; markets also include consumption, interestingly enough. Between the two lies the transaction, including all of the costs of conducting the transaction. These, as the economist Kenneth Arrow laid out, are the costs of running the economic system. More than production, the panoply of transaction costs determine the structure of firms and the economic structure of a society.

As I see it, this is the world that the author envisions:

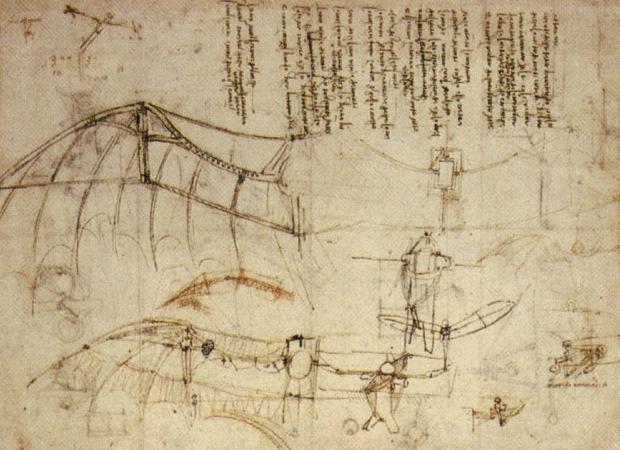

Da Vinci’s flying machines were both technically dazzling and fueled by state intervention via the Medici family. But it took a couple of bicycle manufacturers, who had experience in materials and engineering to actually create the first flying machine. And the Wright Brothers too were not the most successful at commercializing the technology. For all of the distrust of commercial society by this strain of the left, at core, commercialization is the democratization of production.

As I explained before, Alfred North Whitehead was probably right about the state of science in Europe in 1500: the total accumulated knowledge was less than Archimedes knew in 212 BC. But as far as applied technology is concerned, the same could not be said. By 1500, Europe had advanced further than known before through small scale commercial means. Although they might not have been more enlightened, they were incomparably better at producing and consuming the goods and services that determine material living standards.

In part, a rise in the productivity of human capital in that time period resulted in new, more efficient modes of production. It is wonder that the author, for all of his mentions of capital, doesn’t have a firm grasp on the important idea of human capital as evidenced by this statement:

At the same time, enterprises in poorer regions, lacking access to high-level R&D, find themselves trapped in a vicious cycle. Their present inability to make significant innovations that would enable them to compete successfully in world markets undercuts their future prospects. Only a handful of countries — such as South Korea and Taiwan — have ever been able to move forward from this starting disadvantage.

What is ever more startling is that the author fails to recognize that North Korea was far more advanced than the South before the war. And, of course, that handful of countries is only a handful if you don’t consider most of Africa or Asia. Nor does it explain why Russia is doing so poorly in spite of all of the state sponsored research in the past. But going down that very sordid literature wouldn’t work especially well with his political outlook. So, I won’t. ** **

First published Apr 3, 2015